Editor’s Note: This article was written by Colin just before the recent unprecedented flooding in Yellowstone, our nation’s first national park. As we reflect on the significance of the upcoming July 4th Anniversary – and the idea that the national parks are the Declaration of Independence applied to the land – the damage and closings that resulted from this disaster make us all appreciate the enduring treasures of our national parks more than ever.

There were no national parks within the range of my traveling capabilities when I was growing up. I didn’t really know what a national park was. The words didn’t evoke any kind of image within my experience. I never visited one until I was an adult. It took me a long time to learn to appreciate what a great thing the national parks are.

I have to credit the Ken Burns-Dayton Duncan film “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea” for opening my eyes to the full magnitude of that idea. I was pretty much convinced of the truth of their thesis, that the National Parks really might be “America’s Best Idea,” after the founding of the country and the formulation of democracy itself.

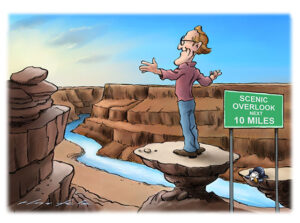

In an interview, Duncan said, “I will make the argument that the national parks is our best idea. And the reason is because it is actually an expression of the Declaration of Independence applied to the landscape, which is that the most beautiful, most majestic, and, I would say, sacred places in our nation should be set aside not for royalty or the rich or the well connected, as it had been in all recorded history, but for everyone and for all time.”

Today the idea has been picked up all over the world. The International Union for Conservation of Nature counts more than 4,000 national parks. And that is good for the whole world. It means that many of the most beautiful places will be preserved for the benefit of all people. It’s a worthy aspiration toward a higher level of society than one that just lets exploiters run roughshod over everything.

The film grew out of Dayton Duncan’s deep passion for the national parks since his childhood. Duncan has worked with Ken Burns on almost every film, either as a consultant, writer or producer, going back to The Civil War. But it seems clear to me, from watching interviews with him, that the film about the national parks was a special favorite for him, and an intensely personal vision.

The national parks have been one of the most profound passions of his life. The film was a chance for him to put that passion into a cinematic expression. His love for the parks is infectious. The film series won two Emmy awards, but even more importantly, I think, its wide viewership when it came out in 2009 was followed by a surge of attendance at the National Parks.

I suppose the series influenced many others the way it did me. I was really taken by the idea that the national parks are the principle of democracy expressed in the landscape itself.

Duncan said that the idea came from writer and historian Wallace Stegner, who wrote an article in 1983 called “The Best Idea We Ever Had: An Overview.” In it he wrote, “National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”

Stegner himself credits James Bryce, a British Ambassador, with coining the phrase. And there may be other legitimate claims to being the first to articulate the idea. But, as with so many things, finding the “first” is probably impossible. Beginnings tend to fade into the mist of the past. But that speaks to the universality of the idea.

In a 1990 article in which Stegner credits Bryce for the phrase, he also acknowledges that “The tracing of ideas is a guessing game. We can’t tell who first had an idea; we can only tell who first had it influentially….”

The idea behind the national parks seems to have come from the population itself, a spontaneously arising movement to protect the most beautiful places from exploitative destruction. That too speaks to it as an expression of democracy. The idea seems to have worked its way up to the governmental agencies that could enact laws to codify it.

It emerged out of a growing awareness that those beautiful places out west would soon be overrun and probably desecrated. It’s an encouraging example of how people who believe passionately in something can actually make a difference, even in the face of powerful forces against them.

The origin of the national parks themselves is also not easy to pinpoint. The website of the National Park Service says, “Artist George Catlin, during an 1832 trip to the Dakotas, was perhaps the first to suggest a novel solution to this fast-approaching reality.”

Indian civilization, wildlife, and wilderness were all in danger, wrote Catlin, unless they could be preserved “by some great protecting policy of government… in a magnificent park… A nation’s Park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

Presidents Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant and Teddy Roosevelt were all instrumental in the development of a national park system. It’s a long and complex history. We are lucky that the idea has managed to survive the political system and to progress as well as it has

When I traveled to some of the great national parks of the American West, I got the feeling that the idea underlying the parks is shared in general by the people who attend the park. Surely, they haven’t all seen the Ken Burns film. But somehow there seemed to be an unspoken sharing of the ideals.

It struck me particularly when I was in Zion National Park, but the same was true of all the parks I visited. People seem to share a kind of reverence for the place, for the environment.

The name Zion refers to a hill in the city of Jerusalem, but it is also defined more generally as “holy place” or “kingdom of heaven.” Once I experienced Zion, I understood why it was called that. It is an astonishingly beautiful place, with colossal mountains and steep cliffs, abundant running water flowing in crystal clear streams. I got a strong sense among the people visiting that they appreciated that transcendent beauty and honored the area as a kind of holy place – a secular spirituality that creates a common ground for people of varying religions to meet on.

I was extremely moved by the spirit of camaraderie I felt and observed there among people who were obviously from many different states and countries and ethnic backgrounds. But the gorgeous landscape, and a shared reverence toward it united everyone in an unspoken pact.

The way people treated others, with kindness and respect, was a revelation. It was as if the reverence for the natural beauty infused our relationships with each other. It did feel like a holy place. And it felt good.

Could that have existed without the creation of the national parks? I doubt it. There had to be an official proclamation that set aside this land to protect it from those who would not honor its beauty and see it as a sacred place.

Another thing the film made clear was that it was always a battle. The protection of those places so that they have survived in good shape up to the time when we could enjoy them is a great blessing. It’s not something I take for granted.

But I am way behind. I’ve visited national parks in Africa, Australia, Scotland, Jordan and other places. And yet there are so many in my own country that I have not seen. I need to try to make up for that blank space in my life story.

Your humble reporter,

Colin Treadwell